Automatic asset allocation rules governing savings and pension plans are driving purchases that appear to make no sense.

By John Authers

June 16, 2021, 12:00 AM EDT

Why Are Bond Yields Doing This???

Last week I raised the question of why bond yields managed to stage a significant decline around the highest inflation reading in decades. We all know the arguments that this is transitory, that the Federal Reserve will stay lenient, and that President Biden will fail to get Congress to deliver a meaningful fiscal stimulus, but these still aren’t enough to explain what is happening. Investors seem needlessly exposed to the risk that those sensible ideas turn out to be wrong.

And while the central bank’s massive intervention has much to do with it, it’s too easy to blame everything on the Fed. As Aneet Chachra of Janus Henderson points out, the U.S. Treasury issued $6.68 trillion in the first four months of this year, of which $1.73 trillion came from bonds of two years maturity and upward. The Fed bought $320 billion over that period, which is a lot, but still left $1.4 trillion searching for other buyers. We know that there must have been plenty of investors who obliged, but what can possibly have possessed them to do so at deeply negative real yields?

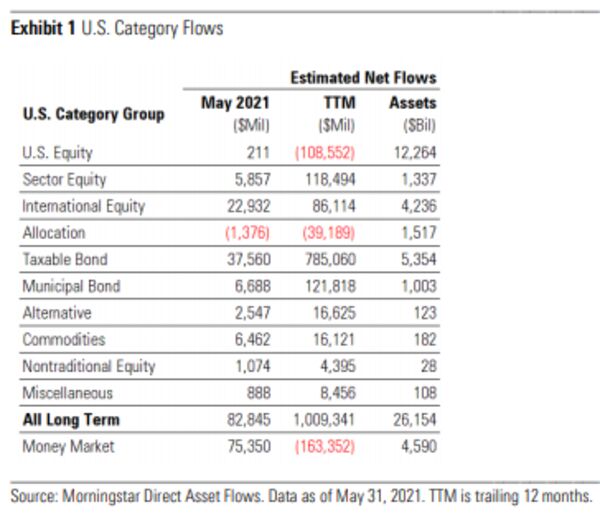

This is when we look at the figures for institutional savings plans. Over the last 12 months, investors have pulled a net $108 billion from mutual funds and ETFs investing in U.S. stocks, while putting an astonishing $785 billion into U.S. taxable bond funds, according to Morningstar Inc. Bear in mind that over the 12 months to the end of May, the most popular stock ETF (SPY) outperformed the best-known bond ETF (TLT) by 62%, so this doesn’t look like great market timing:

What can possibly have driven such enthusiasm for bonds over the last 12 months? Are people mad? Chachra picks up the story:

Several years ago, my wife and I started contributing to a 529 educational savings plan for our two kids. Given the long time horizon and high tuition inflation, I selected the aggressive allocation option. But when I recently checked the quarterly statement, I noticed the account was in a mix of equity and bond funds. As our kids got older (they are now 9 and 11), the provider automatically moved them into a 70% equity/30% bond allocation. And as equities rallied over the past year, the plan periodically sold stocks and bought bonds to maintain the target ratio.

It turns out that I’m among the investors buying low-yield bonds. Also, about 5% of the account is allocated to a diversified international bond fund. Roughly 60% of its holdings are in Japan/Europe, so we’ve been inadvertently investing 3% of our kids’ educational savings in no-yield bonds.

In this 529 plan, I can override the pre-set allocation rules and choose a different weighting to stocks and bonds. But I still have two uncomfortable choices. With stocks I take the risk that they decline sharply in value immediately before our kids start college. With bonds I’m accepting a likely below-inflation return.

Automatic asset allocation funds are in general a good idea (or at least, you will be able to find plenty of statements to that effect from me over my career). They effectively force people to adopt dollar-cost averaging and use a simple version of market-timing, in which they sell assets that have recently risen in price, while buying those that have fallen. Personally, thanks to the beautiful numerical language of American retirement planning, I have both 401(k) and 529 plans tied up in target-dated funds. That means that I, like Chachra, bought a big slug of stocks last spring (which is a good idea), but also that I have been making steady sales of stocks while buying into bonds ever since.

Regular readers may be aware that I don’t necessarily think this is a great idea. Taking regular profits from stocks at this level makes sense to me, but not if I then put them straight into even more overvalued bonds.

More direct regulatory pressure has had an even more dramatic effect on defined benefit, or DB, pension funds in Europe. To their credit, regulators grasped several years before the financial crisis that there was a risk DB plans wouldn’t be able to meet their liabilities, and so required them to adopt “liability-matching” — which in practice meant buying more bonds to make sure they could cover their guarantees.

This means that Britain faces much less risk of widespread pension defaults than the U.S, which is a real and important achievement. But it has come at a cost. I recommend this piece in the Financial Times by my former colleague and mentor Martin Wolf, in which he proposes radical pension reform. He says:The demand that DB schemes be made as risk-free as possible has also had a dramatic impact on their ability to hold the riskier assets that offer higher long-term returns. This makes meeting pension promises still more expensive. Between 2006 and 2020, the weighted average share of DB portfolios in equities fell from 61 to 20 per cent and the share of UK quoted equities in that total fell from 48 to 13 per cent. So, the latter make up just 3 per cent of DB portfolios.

This may have saved savers from disappointment, but it has done it very expensively, and has helped prop up bond markets at extreme valuations. In a way, this is a form of financial repression; the effect of regulatory action to make savings safer has been to increase the cost of pension guarantees and (by depressing bond yields) make government financing costs much cheaper. One way or another, we’re going to lend money to Uncle Sam, or Her Majesty’s Government, or other governments around the world, at dirt-cheap rates. Whether we like it or not.

F!O!M!C!

The big event of the week is upon us. The Federal Open Market Committee, which decides on monetary policy, is meeting and will release a statement at 2 p.m. East Coast time, along with a raft of new projections. Then Jerome Powell will give his regular post-meeting press conference. Some kind of acknowledgement of last week’s startling inflation numbers will be necessary. Precise choice of words could have a market impact. But Powell doesn’t need to do anything. The odds of any change to monetary policy, beyond technical adjustments, are tiny.

Despite the highest inflation number in almost three decades, Powell has plenty of justification for staying the course he has set, if that is what he wants. Unemployment hasn’t improved as much as hoped in the last few months, and much of the increase in inflation is obviously “transitory,” to use the word of the moment. Further good news, as far as the Fed is concerned, is that bond yields have fallen in the last three months; even given the factors I mentioned above, this shows there is still a presiding belief that the Fed will stay “lower for longer,” and won’t be panicked into tightening policy.

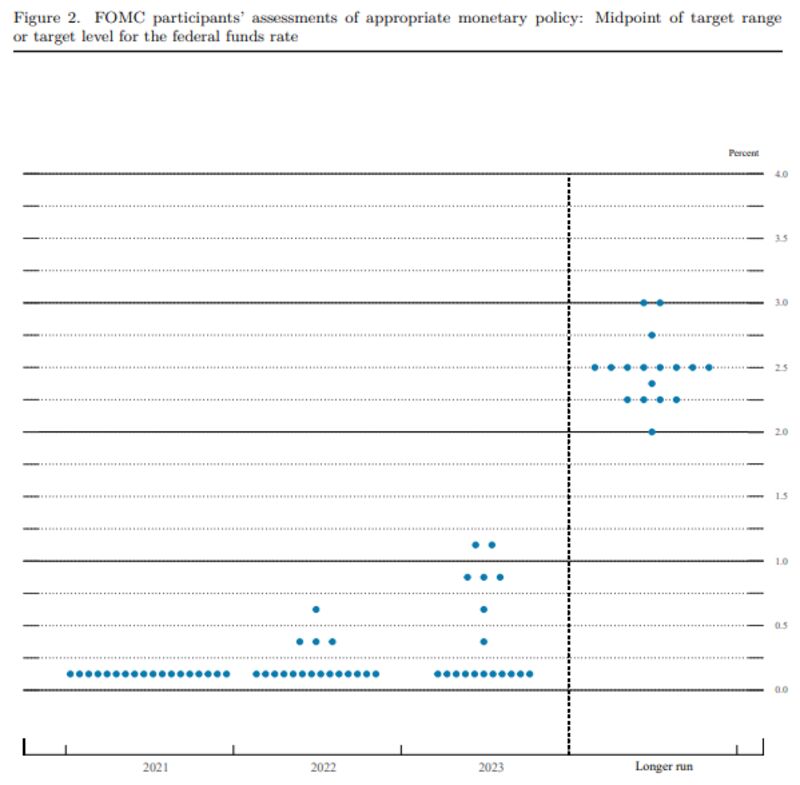

The “dot plot” on which governors show their economic projections, might conceivably show that that the median prediction for when rates start to rise has been brought forward. As it stands, 11 of the 18 voters say rates will be unchanged by the end of 2023. Therefore, if two or three edge up their predictions from there, the median projection for the first hike would move closer:

How much does this matter, really? Not a lot. Most of us can work out that this is fairly balanced, and that a lot can happen in the next two years. Besides that, the Powell press conference, and later the publication of the meeting’s minutes, will give plenty of opportunity to cast this in a dovish light. Words, for now, still matter,

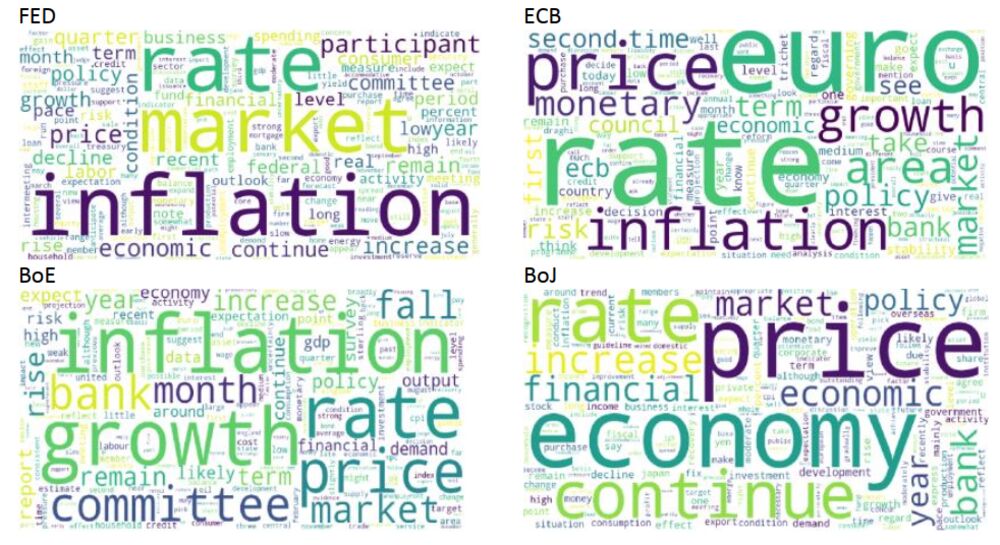

And when it comes to words, classic number-crunching techniques are being used to analyze central banks’ pronouncements. Oxford Economics produced word clouds of those that recur most frequently in communications from the Fed, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan. Here they are, and they show some interesting differences:

It’s maybe not surprising that the BOJ never mentions inflation, but it’s interesting that the ECB seems less concerned than the Fed or the BOE. It’s also intriguing that the ECB cares a lot about the euro while none of the other big central banks ever say much about their currencies. The BOE is bothered about growth; and it is telling that one of the BOJ’s favorite words is “continue.” Maybe we should expect Japan’s slow economy to continue.

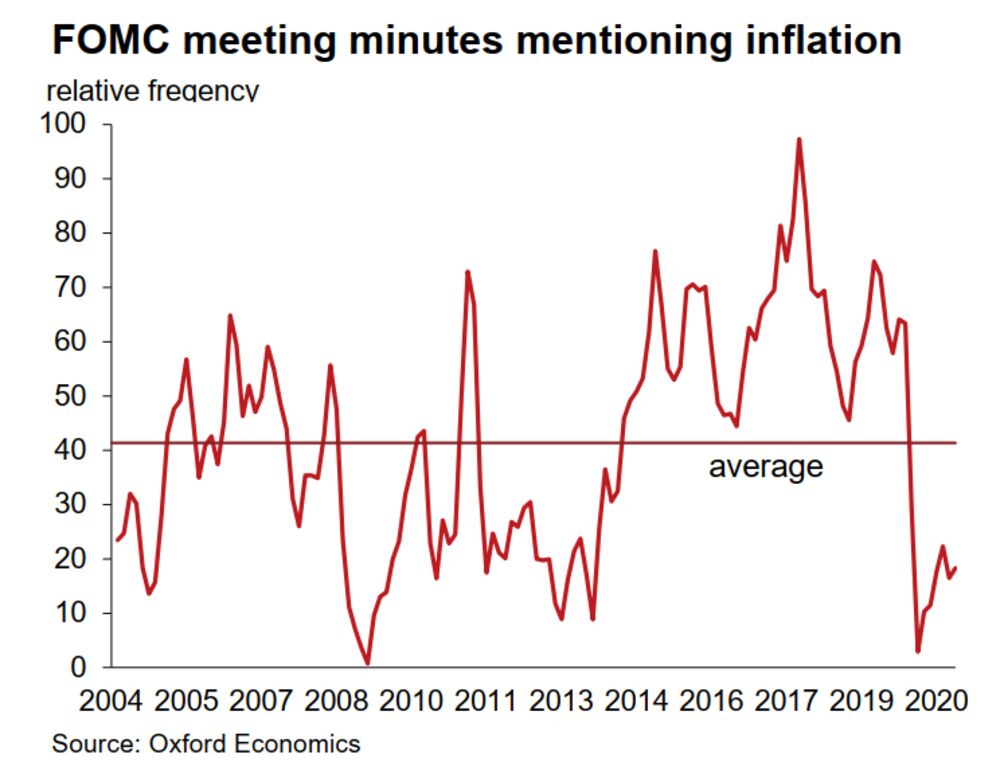

As for the Fed, even if it talks more about inflation than the ECB, it still doesn’t talk about it much. The FOMC seemed more worried about it at the top of the brief boom created by the Trump tax cuts, when it embarked on a policy of quantitative tightening, or steadily reducing the number of assets on its balance sheet. That concern almost vanished during the pandemic, and remains low, as Oxford Economics shows:

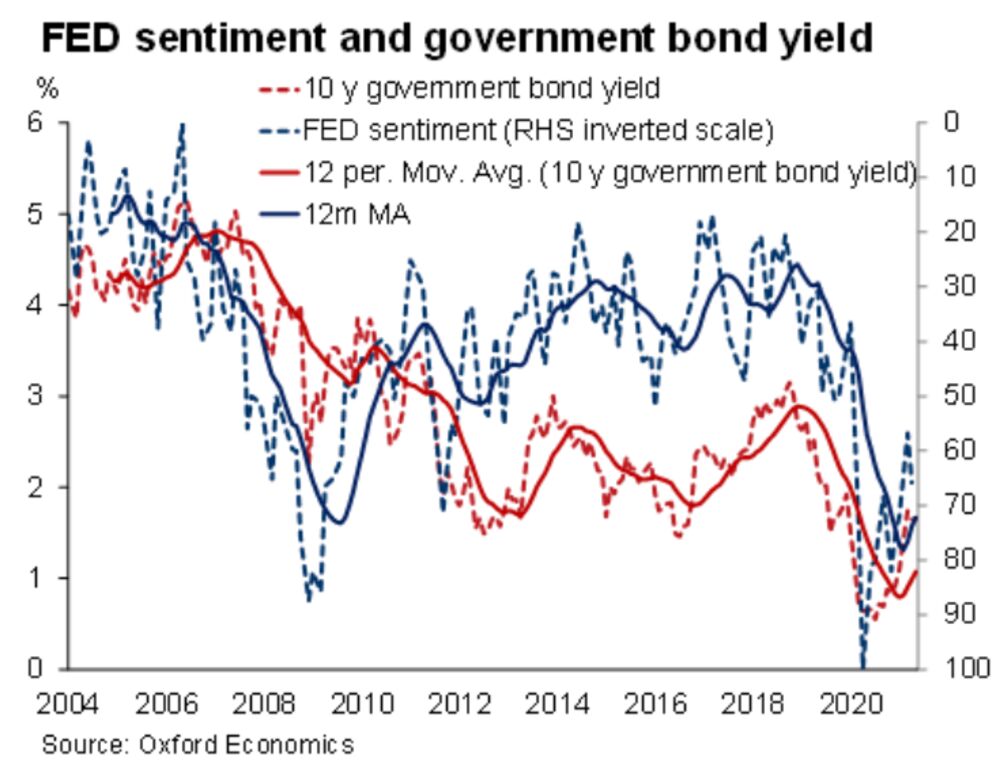

The implication is that FOMC members really are prepared to look through rising inflation for a while longer. And if all this work analyzing word choices seems a little excessive, Oxford Economics’ Fed Sentiment indicator, produced via machine learning analysis of Fed transcripts, does seem of interest. When the Fed’s governors appear particularly agitated, the chart shows, yields tend to drop, and the relationship has grown a lot closer in the years since the global financial crisis:

In principle, it’s not surprising that the bond market has cleaved more closely to Fed sentiment in the last decade, as the outlook for continuing support has grown ever more important in these weird conditions. And if we return to the puzzle of why bond yields stay so low, it may well be because investors are doing a good job of gauging the central bank’s thinking. So as we all brace for FOMC Day, the bottom line is that we shouldn’t expect any great change of course; but that the intense efforts to parse every word may actually be justified.

No comments:

Post a Comment